I did not plan on this being my first topic covered on this blog. I have grand ideas of responding to theological works and reading things that challenge my perceptions. I still do. As it happens, however, my perceptions were challenged unexpectedly by a movie I just watched. Not challenged in the way that I felt they were pushing against me, but challenged in the way that you feel when someone sincerely asks how you’re doing when you’re in a hurry. A comforting challenge. One that makes you believe that the world is kinder than you expect. This is how I felt when watching Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind. Nausicaa, to me, is a perfect example of an idea I’ve been toying with for a while: great fiction provides us with stories worth believing.

When I first decided to become a teacher, I did so as someone acknowledging my tendency towards pessimism. I find it exceedingly easy to find flaws in the world order, in myself, and (I am ashamed to admit) in others. Yet I found that my lens changed when I worked with kids. I was inspired by many children’s excitement at the wide world in front of them. Proximity to them and their excitement drew out my ability to see the good. I find that I cannot look at a child and see failings. I see potential and growth. I do not think I am alone in this experience because I see the same instinct in the stories we tell children. We tell children stories of good triumphing over evil, of kindness being rewarded, and heroes that face their fears. We tell them stories that would make them better people if they believed them. I teach because I want to help them discover those stories.

At some point in 6th grade, I put down my Percy Jackson and Harry Potter books and picked up Divergent and The Hunger Games. I, as all middle schoolers do, had unlocked the metacognitive ability to be scared of every possible thing. Therefore, I had to retreat from loving stories of magic and paragon heroes (those were too colorful and unabashedly joyful) and confide in the world of teen dystopias. I could still read those fantasy books, but there was something so alluring about dystopias when I was feeling like the world was out to embarrass me and make me lose whatever social status I had. But here’s the catch: no one was out to get me. I remember a friend telling me early in high school, “we’re at a weird age where we like girls and Nerf guns.” Maybe if I were to twist his phrase to talk about the stories we believe in, I could call this period of life the time where we like magic and know sometimes magic doesn’t work. We love enchantment and become disenchanted. Or at least, I did.

Again, no one was out to get me. I am increasingly convinced that most humans really want to do good, we just have a limited capacity to succeed at it. People are kind but they’re also scared. In some way, the same me that stopped reading fantasy in favor of dystopias is the me that comes out when I mutter hateful words under my breath when someone cuts me off in traffic. It’s not that I really hate that person— I want them to get to their destination safely— I just reacted because I was afraid they’d hurt me.

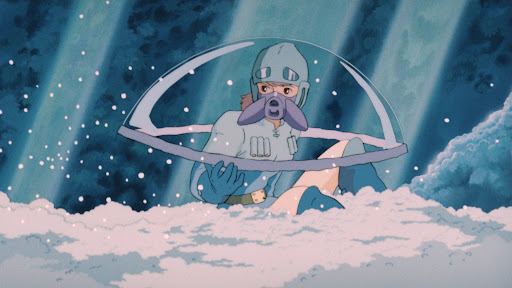

In Nausicaa, the titular character faces fear. She’s the princess of a post-apocalyptic village on the outskirts of a nuclear wasteland, called the Toxic Jungle, which is characterized by toxic spores in the air and massive territorial insects. Just outside the bounds of her village is a land where many things can easily hurt her. Her response to this reality is shown in the film’s first scene, where she explores the Jungle. There, the spores fall like snow as she rests on the carcasses of dead insects. The animators make a vibrantly colorful and textured setting, and musicians create a lively score. This is how Nausicaa experiences the world. She daydreams of a reality where this beautiful land is a place she could stay in more sustainably, but she’s awakened to action when she sees insects attacking another explorer. While the wasteland is beautiful, it is a place where humans have very little control.

Despite her limited control, Nausicaa always acts for the defense of other humans. When the other wasteland explorer is attacked by insects, she hops on her glider to come to his aid. Nausicaa carries a gun on her, but she instead uses flares and sounds to redirect the insect. She flies close to the insect and uses a noise-making tool to allow her to talk to the insect and command it to return to the jungle. Upon her return to the valley, she finds a mentor returned with stories and a creature who, although a baby, is already vicious and will continue to be as it grows. Yet Nausicaa reaches her hand out for the creature to crawl on her. Though it bites her, she only thinks of it as scared, and by the time it releases its bite, it feels safe to lick her finger affectionately and is her companion for the rest of the story. Her mentor names this as a strange power she has. In these events, we see Nausicaa not only act for the defense of humans but for the good of all the creatures she interacts with, even when she has good reason to fear them.

Providing the counterexample to Nausicaa are the people of the Torumekian Empire, invaders of the hero’s home in the Valley of the Wind. The Torumekians arrive seeking the dormant body of a Giant Warrior- a superweapon from a thousand years before whose attacks created the Toxic Jungle (a metaphor for the effects of nuclear weapons, but that’s outside the scope of this essay). The Torumekians wish to revive the Giant Warrior and use its power to burn away the Toxic Jungle and return humanity’s control over the Earth. Under all of their actions lie fear and ambition. They fear their vulnerability in a world where they’re prey to insects and victims of toxins. They fear death at the hands of these things they do not control. Their ambition is tied to this fear, as their ambition is to regain the control humans had before the apocalypse. Ambitious control, however, proves to be the incorrect response to fear in the world of Nausicaa.

Nausicaa intuits that there is a greater response to fear, as we see a childhood flashback where she hides a baby Ohm, the apex predators of the insects, as people from the Valley of the Wind search to kill it in order to defend their land. Not only does she intuit this, but she also learns that the Jungle is not something to be lashed out at in fear when she escapes captors who were leading her to the Torumekian capital. She crashlands into the Jungle and sinks to depths below the Jungle floor. There she finds no toxic spores, but instead remains of petrified trees that are safe and create the pure waters used for wells. These are the oldest parts of the Jungle, which have exuded their toxins borne of the Giant Warrior and are now good to sustain life. The Jungle is, in its own way, experiencing fear. The Jungle is toxic only because it was attacked. It must defend itself to live, but once it has let out its toxins, it can sustain life once more. Instead of continuing the cycle by fighting back against the hurt Jungle and making it more toxic, Nausicaa learns that the humans must live with the Jungle and let it heal, finding ways to survive alongside their deadly creation.

The competing ideologies of Nausicaa and the Torumekians come to a head in the film’s climax when an uncountable horde of Ohms stampede towards the Valley of the Wind, enticed by a 3rd nation who baits them with a wounded Ohm baby. At the time of the attack, Nausicaa is still deep in the Jungle and racing to return home. This leaves the Torumekians in charge of the Valley of Wind. While the Giant Warrior is not fully ready, the Torumekian princess decides that awakening it is their only defence. Upon its appearance, the awakened Warrior is evidently incomplete. Its appearance is like melting wax, and its movements are slow and labored, but the Torumekian princess orders it to fire its laser beam on the Ohms anyway. Creating a mushroom cloud explosion, the beam kills many Ohms, but the princess is not satisfied, ordering the Warrior to fire again— and faster this time. Though the Warrior gets one more beam off, the effort melts the rest of its body, rendering it unable to continue its attack. While the princess raised this Warrior to be humanity’s salvation from the Toxic Jungle and its insects, she used it hastily as a control-seeking response to fear. In doing so, she ruins her efforts.

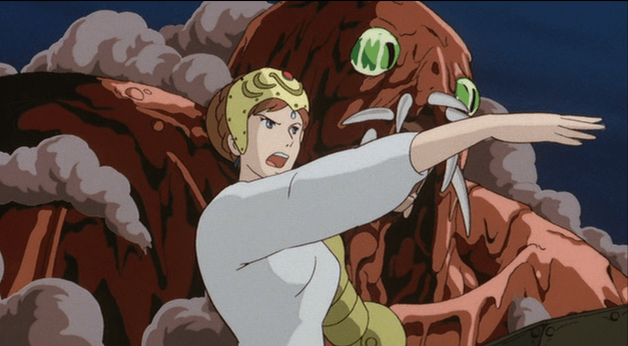

Nausicaa’s response to the Ohm stampede in the climax is the story’s heroic response to fear. She identifies the baby Ohm as bait and is filled with compassion for it. She recognizes that not only is the baby suffering as a captive, but that the stampede of Ohms are suffering in their blind rage. She is not void of fear; she knows that the Ohms are bound to destroy her beloved home and people she has worked to protect if the stampede continues, but her experience in the Jungle has taught her that the world is seeking restoration, not simply to attack humans. Restoration, she knows, cannot happen if humans continue angering the Ohms, so she must find a way to protect the humans without harming the Ohms. Ultimately, she flies in front of the Ohms to free the baby and dies in the stampede. The Ohms, recognizing her sacrifice, cradle her and bring her back to life, then return to the Jungle to care for the baby.

In Nausicaa, the world is hurt. It has been harmed by humans who use power in search of control because they are unwilling to confront their own fear in any other way. In return, it acts in ways that harm humans. The hero, though, is the human who confronts her fear with the perspective of acknowledging others’ fears. She knows she can be harmed, but she also knows that she is capable of harming the world around her. In response, she chooses compassion. She shields the weak and vulnerable of both her own people and of the Ohms, and in turn, she is able to create greater peace for both.

I love this story, and many like it, because I love its world. It is a place where goodness does not necessarily beget goodness, but where goodness, particularly the forms of courage and compassion, is rewarded as a virtue. This does not mean Nausicaa’s life is easy because she’s good. In fact, the dystopian world she lives in has all the harshness of our own. She loses loved ones. She’s betrayed. She can’t protect all the people she wants to. She dies. The Jungle is not destroyed. Yet the narrative shows that her goodness was the only way forward. If not for Nausicaa’s sacrifice, her village would die. If she held herself with any less courage or addressed her fears any other way, then the story would not end with peace. Nausicaa does not get a rosy ending. People still died. The Jungle still expands. She does, however, get an ending with hope. She knows the way to restoration. She will not see the world restored in her lifetime, but if others follow her example, the Jungle will recede and the world will cease to hurt as it does now.

Nausicaa’s challenge to me was to believe in a world kinder than I expect it to be. I picked up those teen dystopias in 6th grade not because they were well written (I’m quite sure many of them weren’t), but because they showed me the world I believed in. Someone really was out to get Katniss. Some days, I still do feel like there’s someone out to get me, but that’s not the world I believe in. I believe in a world where goodness may not always lead to positive outcomes, yet that humans acting in goodness is the only way forward. I believe that there is something fundamental in the fabric of our world that seeks restoration, and that goodness is worthwhile because of it. I believe in a Creator who is continually working the Jungle into a healed world. And I believe so many others deeply want to believe in that reality; that’s why we tell these kinds of stories to our children. We want them to believe the world is that way. We want them to know that Good is coming. When we are no longer children, however, these stories speak no less truth. In fact, I find I need them all the more when I do not have the vision to see my own world as good. Perhaps it is only escapism, or perhaps these stories remind me to believe that my world’s story is one worth believing in, too.

Thank you for reading my first essay on this blog! Nausicaa’s story was a comforting encouragement to me as I watched. As I was writing this, I was reminded of the song “The Helpers” by Paper Horses- a song about a real world source of continued encouragement, I highly recommend it 🙂

Leave a comment